From article:

How to Eat According to Your Carb Tolerance

There’s no single solution for eating the right mix of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Here’s how to find your personal optimal mix to get fit and have great energy.

A Brief Summary of The Carb Wars

From the mid-20th century up until the 1990's, the standard medical dogma was that low-fat, high-carb diets were the way to go. It helped that the arguments in favor of this diet were very straightforward: fat has nine calories per gram, while carbohydrates only have four, so fat should be much easier to overeat. Additionally, dietary fat can be transported straight to your fatty tissue for storage, while dietary carbohydrates have to be processed by the liver. So eating fat should, it seems, lead to fat gain more easily than eating carbohydrates.

Beginning in the 90’s, opinion began to swing in the other direction, towards low-carb dieting. Low-carb advocates like Dr. Atkins pointed out that dietary fat is necessary for satiety and steroid hormone (testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, etc) production, and is also needed for structural uses—our brains are largely made of fat, for instance.

The low-carb movement blamed high carbohydrate intakes for the modern obesity epidemic, arguing that eating carbohydrates causes your body to produce insulin, and insulin causes your body to store energy in fatty tissue. Therefore, carbohydrates are more fattening than fat, on a calorie-for-calorie basis. They further blamed insulin for making carb-eaters hungrier, causing them to overeat.

This argument contains two major flaws. First, insulin is an energy storage hormone which acts on all body tissues, not just fatty tissue—it also causes your muscles and vital organs to store energy. Second, insulin actually suppresses appetite by ensuring that the brain is adequately supplied with energy.

The Surprising Science of Carb Tolerance

Unsurprisingly, the low-fat vs. low-carb question has been studied to death. Many studies find low-carb diets to be superior, but that seems to be because low-carb diets tend to be higher in protein content. When low-carb and low-fat diets with similar protein contents are pitted against each other, they tend to produce very similar results, on average.

However, “on average” is a hugely important caveat. Individuals vary tremendously in their response to low-fat and low-carb diets, so there is no one-size-fits-all answer here.

Several studies have found correlations between blood markers of carbohydrate metabolism and response to high-carb vs. low-carb diets. People with elevated fasting blood sugar and insulin levels tend to feel better and lose more weight on low-carb diets, while people with normal blood sugar and insulin levels are usually better off eating their carbs.

Of course, tests that you do with a typical home blood glucose meter can only tell you so much. They only give you a snapshot of your blood sugar and insulin levels at a single point in time, and only look at some of the factors that determine your carbohydrate tolerance. I’ve had my blood sugar tested a few times, but I don’t rely on it to gauge my carbohydrate tolerance, and I don’t usually urge my clients to get theirs tested either.

In practice, there’s a better and easier way to gauge your carbohydrate tolerance.

The Simple Self-Experiment to Determine How You Should Eat

I’ve devised a simple way of gauging your own carbohydrate tolerance that I recommend to my clients. Because your gut feeling for how you should be eating isn’t very accurate, you get better information by collecting actual data. The way you acquire that data is through a controlled self-experiment.

What you’ll do in this experiment: eat a few meals of different types with three different carb/fat balances, under controlled conditions. After each meal, you’ll measure things like your mood, hunger, and energy level to see which meals make you feel the best.

Here’s a step by step guide for running the experiment.

Step 1: Decide what time of day to eat your test meals

Although you probably eat three meals a day, you should pick just one of those meals to be the one you run your experiment on. As with any experiment, you need to control as many variables as possible, including what time of day you’re eating— so you’ll also want to standardize the time at which your test meals take place. For instance, you might run your tests at breakfast at 8 AM every day, or lunch at 1 PM, or dinner at 6 PM.

Of all these options, I recommend choosing breakfast if at all possible, because it allows you to control for another set of variables: what happened earlier in the day. Breakfast, more so than lunch or dinner, tends to take place under the same conditions almost every day.

Step 2: Determine the macronutrient amounts for each variation

In this experiment, you’ll be testing three diets: low-carb high-fat, low-fat high-carb, and moderate-carb moderate-fat.

After that, you may also want to test other, more specialized diets, like ketogenic, paleo, vegan, or a protein-sparing modified fast. But start with the first three. These can be sustained indefinitely, and don’t require you to completely avoid any particular food. Your results on these three variations will also be helpful information in considering further specialization, should you decide to do so.

You should test each diet at least three times—so your experiment will take at least three days for each diet you’re testing.

We assume that you eat three meals a day, are moderately physically active (light workouts a few days a week), are in pretty average shape, and want to eat to maintain your current weight. Here are some guidelines for what the test meals should look like — for a person who weighs 180 pounds, and for a person who weighs around 130 pounds:

Moderate-fat, moderate-carb:

- 180 pounds: 50 grams of protein, 35 grams of fat, 90 grams of carbs

- 130 pounds: 35 grams of protein, 25 grams of fat, 75 grams of carbs

Low-fat, high-carb:

- 180 pounds: 50 grams of protein, 10 grams of fat, 150 grams of carbs

- 130 pounds: 35 grams of protein, 5 grams of fat, 125 grams of carbs

Low-carb, high-fat:

- 180 pounds: 50 grams of protein, 60 grams of fat, 30 grams of carbs

- 130 pounds: 35 grams of protein, 45 grams of fat, 25 grams of carbs

Note that all of these meals are moderately high in protein, adding up to about .8 grams of protein per day per pound of bodyweight. But we’re keeping the amount of protein consistent: the scope of the experiment is just about fat and carbs.

Of course, you can and should scale these numbers up or down to account for your actual body weight. You don’t need to get too hung up on the exact size of the meals though—it’s okay if they’re a bit bigger or smaller, as long as they maintain roughly the same ratio between protein, fat and carbohydrates as the examples given.

Step 3: Plan your meals

Once you’ve figured out the nutritional contents for your meals, it’s time to plan the specific foods you’ll eat each day. Again, you’ll need at least three meals of each type.

I recommend pre-planning all of your test meals before you start the experiment.

Here are a few examples of each type of meal:

Moderate-fat, moderate-carbohydrate meals

Meal 1: Three soft tacos with beef or pork, cheese, cabbage, and beans. No rice or sour cream.

Meal 2: Club sandwich with wheat bread, chicken, bacon, tomato, and light mayo. Side salad and cup of fruit.

Meal 3: Pulled pork sandwich with two slices of wheat bread and 5 oz pork, 4 oz mac and cheese, 4 oz broccoli, and an apple.

High-fat, low-carbohydrate meals

Meal 1: 6 oz salmon fillet, 8 oz stir-fried vegetables, 4 oz of blueberries

Meal 2: 3 eggs scrambled with ground beef, tomatoes and avocado, 3 oz of strawberries, 3 oz of carrot sticks dipped in peanut or almond butter.

Meal 3: 6 oz of meatloaf with ketchup, side salad with oil or ranch, half an avocado, handful of mixed nuts, one baby orange.

Low-fat, high-carbohydrate meals

Meal 1: Chicken burrito with rice, cabbage, and beans- no cheese, sour cream or avocado. Can of sugared soda or 4 oz of fruit.

Meal 2: 3 eggs scrambled with turkey, lettuce and tomatoes. Small bowl of cereal. Glass of juice.

Meal 3: 8 oz pasta with 5 oz chicken or shrimp, tomato sauce, 6 oz mixed vegetables, and a small piece of fat-free chocolate.

Each of these meals are sized for someone who weighs around 150–160 pounds and is moderately active, and comes out to somewhere between five hundred and seven hundred calories. Scale up or down as needed.

Step 4: Run your experiment

Before you start your experiment, you’ll need a system to track your results. Create a spreadsheet that looks like this:

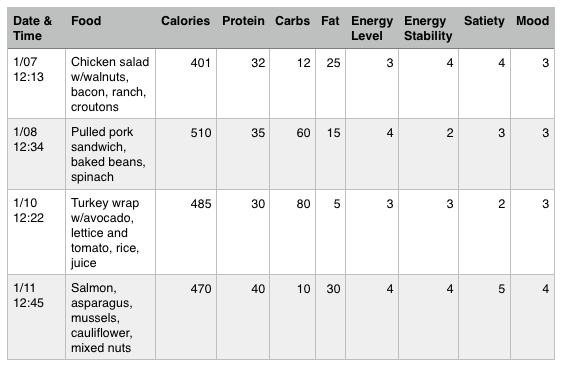

Each row will be used to record one test meal. Here’s what each column means:

Date and Time: when you ate the meal.

Food: what you ate. Be as precise as possible. “Meatloaf” is not very precise. “6oz meatloaf with 2 tbsp ketchup” is much better, even if the numbers are only guesstimates.

Calories: The number of calories in the meal. Use the calorie-counting app of your choice, or if you need to estimate calories, remember that there are 4 calories per gram of protein and carbohydrate, and 9 calories per gram of fat. (More suggestions for figuring out calories are below.)

Protein, Carbs, and Fat: Protein, carbs, and fat in the number of grams—not calories—of each macronutrient the meal contained.

Energy Level: How much energy you have in the two hours or so following the meal. A “1” would mean you feel sleepy, while a “3” would be a fairly average energy level. A “5” would represent the highest energy level you can realistically experience without stimulants—think “I really want to go for a walk or hit the gym,” not “I just had two energy drinks and now I’m bouncing off the walls.”

Energy Stability: How stable your energy level remains for the six hours or so following the meal, or until your next meal — whichever comes first, and regardless of how high your energy level is overall. For instance, if you feel hyperactive one hour after the meal and sleepy two hours after that, that would be a high energy level but low energy stability. A “5” here represents no noticeable variations in your energy level, a “1” would mean you had a pronounced peak and crash — or crash and recovery — and a “3” would mean you had noticeable but not overly uncomfortable variations in your energy level.

Satiety: How long you go without feeling hungry again. A “1” would mean you feel hungry again within one or two hours, a “3” would mean you feel hungry again within about four hours, and a “5” would mean you don’t feel hungry for six hours or more. Note that if the meal doesn’t satiate your hunger in the first place, it likely just wasn’t big enough.

Mood: How calm and happy you feel over the six hours or so after the meal. A “1” means you feel mildly (non-clinically) depressed, a “3” means you feel good but not great, and a “5” means you feel amazing, almost bordering on hypomanic.

You’ll need to remember to fill out this spreadsheet after every meal. It may help to set several alarms on your phone throughout the day, scheduled to go off shortly after the times when you typically eat your meals.

Here’s an example of what the spreadsheet might look like when filled out. In this example, the person getting these results probably responds better to a low-carb diet—although, of course, they’d still want to run the experiment completely to be sure.

As mentioned earlier, you’ll need to eat at least three meals for each diet you’re testing, which means at least nine meals in total. That means the experiment will have to run for at least nine days — and possibly longer — before you can analyze your results.

Step 5: Analyze your results

At the end of the experiment, you should have at least nine meals recorded, each of them on different days, at roughly the same time of day.

Look at the last four columns- energy level, energy stability, satiety, and mood. The best diet for you will be the one that most consistently gives you 4's and 5's in those categories—that’s the diet you should be eating.

Troubleshooting the Experiment

Here are a few common issues people run into, and how you can deal with them.

What if I can’t eat my meal at the usual time or under the usual conditions?

Suppose you’re using breakfast as your test meal, and you usually eat breakfast at home, around 8 AM. But one day, you have early morning meetings and you need to either eat breakfast an hour and a half earlier — and also wake up an hour and a half earlier — or else eat something in the car as you drive to work. What would you do?

The best answer here is to just skip that day. You can always pause the experiment and not have a test meal on any given day if life gets busy and something happens that would disrupt the experiment. It’s better to let the experiment be delayed a day than to let something happen that would confound the results.

What if I don’t know the nutritional content of my food?

First off, this is a good argument for eating the test meals at home. Try your best to buy food with nutritional labels.

That said, you can estimate the nutritional content of your food pretty closely. Measure everything in measuring cups, measuring spoons, or even using a food scale. Look up nutrition data with Google, or the SELF nutrition database.

And remember—you don’t need to be exact. As long as your numbers are within about ten percent accuracy, it’s close enough.

What if two diets are tied for first place?

Run the experiment a little longer. Drop all other diets from the experiment, and test the two possible winners for two or more meals each.

It might also be that your diets aren’t different enough from each other. Remember that the “moderate” diet should have about two or three grams of carbs per gram of fat, the low-fat diet should have ten or more grams of carbs per gram of fat, and the high-fat diet should have almost two grams of fat per gram of carbs. You may need to make your low-fat and high-fat diets a little more extreme to clearly differentiate them.

What Happens When You Eat For Your Carb Tolerance

The odds are, you’ll find out that you’re pretty average. Most people, myself included, feel their best when they eat a moderate-carb, moderate-fat, high-protein diet—which is still a bit lower in carbohydrates than the average American diet.

Almost everyone feels best eating high protein, regardless of their fat/carb balance.

But maybe you’ll be different. Remember Steve from the beginning of this article? After running this experiment, it became clear that he suffered major blood sugar crashes after high-carb meals. I had him limit his carbohydrate intake to 120 grams on workout days and 60 grams on rest days.

He went from feeling tired and grumpy every day to being happy and full of energy—and lost 40 pounds in 4 months. His carb tolerance has since improved somewhat, but he’s still at his best when he keeps his carbohydrate intake on the lower side.

Jenny, another client of mine, had been limiting carbs in order to prepare for a bikini competition. She was already very lean and exercising at a high-intensity level for about ten hours a week. When she ran the experiment, she found she had way more energy when she added some healthy carbs like rice, beans, potatoes, and fruit to her meals.

She didn’t go super-high on carbs, but by upping her carb intake by about a hundred grams a day, she was able to train harder and put on several pounds of muscle without gaining fat. Her sleep also improved, and she gradually started to feel more cheerful once her body was no longer starved for energy.

People benefit from individualized diets due to a phenomenon called nutrient partitioning — eating the right diet for your body causes more of the calories you eat to go to your brain, muscles, and other vital organs, and fewer calories to go to fat. More calories to your brain — as well as your heart, liver, and lungs — means you’ll have more energy, feel more alert, and be in a better mood.

Different people respond better to different diets due to a combination of factors: genetic, hormonal, and body type. There is no one diet that will work best for everyone, and many people spend years, or even their entire lives, on a diet that doesn’t really work for them. You don’t have to be one of those people.

By spending a few weeks up front experimenting with different diets, you can figure out which one is right for your body. And when you’re on the right diet, you’ll feel better, perform better, live longer, and find it dramatically easier to lose fat and build muscle.

Thanks to Terrie Schweitzer.

No comments:

Post a Comment